| | Hafan Home | | | | Chwilio Search | | | | Hanes a dogfennau History & records |

|

I WONDER if any one ever saw an elephant in a menagerie for the first time, or indeed at any time, without thinking how hideously ugly he was. Of all the strange creatures that come over the sea to be shut up in Zoological Gardens, or to be dragged about the country in wild-beast shows, the ' Sagacious Elephant ' of all the story-books is certainly the most repulsive and unnatural to our English eyes. Almost all other creatures are like something we have seen. The bison are bulls, the zebras donkeys; lions and tigers are only ' great cats;' but what in all the Western world was ever at all like an elephant ? He looks such a huge, shapeless, half-alive creature, his head always too big for him; and his skin, too, as it hangs in folds, like a covering of dingy leather, which wanted tightening to make him at all tidy; and I believe, poor fellow, that is just what it does want. The elephants one sees, in country shows especially, have only just food enough to keep them alive, for hay is dear, and green food not to be had in the immense quantities required by such a huge vegetarian, and so the poor great beast, humble and gentle, and sleepily contented as he always looks, is generally really half starving; and his untidy-looking skin would be much more tight and trim about him, if he only had flesh on his bones to fill it out. But the most wonderful, and also the most disagreeable thing about him is his snake-like trunk. It does not at all reconcile one to think of all the extraordinary things he can do with it; it only makes it more disagreeably unnatural) as it comes stretching out like a huge black-grey boa-constrictor over one's shoulder, when its owner, the great monster, ever so far off, has sent it to hunt for gingerbread-nuts amongst the crowd. Faith, even in the wisdom of the huge beast, is rather shaken when one sees that he is utterly absorbed all day long in his prospects as to those very gingerbread-nuts. He is thinking of them, and them only, as he sways his proboscis over the heads of his visitors; one can see the twinkle of his eyes as he keeps it waiting near the hand of a possible benefactor, and then a look of stolid satisfaction as he sweeps up the tiny scrap at the end of his trunk, and carries it aloft on its way to the hideous mouth waiting wide open for it—waiting so wide open, that he looks as if he could swallow half his company as easily as the cakes which he puts so daintily far down the depths of that ugly red cavern.

This, then, is the sagacious elephant, the grandest, and wisest, and often the gentlest-natured of all living creatures. And he is all this, grotesque and ugly as he looks in his square wooden box, where neither his strength or cleverness or beauty can possibly be seen properly. He stands there stupefied by captivity and idleness, sometimes, I am afraid, too, by hunger, a poor fellow to whom even bits of gingerbread may be an object. He is out of his element, or rather a picture out of all keeping; he wants only another and a grander background, to show that he, too, has a wonderful beauty of his own. But then, you must forget him as a wild beast in a menagerie, and think of the stately creature of many a pageant in the gorgeous East.; or, better still, put him back in fancy, where he will never, poor fellow, be again in reality, in the depths of his own Cingalese forests. There he becomes a part of all that wealth of life, that almost overwhelming splendour of beauty, which makes descriptions of a tropical forest like the tale of an enchanter's dream. There the trees are all of strange forms, fan-like foliage throwing sharp depths of shadow in the blinding sunshine ; often wreathed by lovely creepers, all blue and gold and scarlet blossoms. Sometimes a sun-shower hangs every leaf and flower with pendent brilliants. Even loathsome things are lovely there. Tree-snakes, with colours like burnished metals, flash like living gems amongst the leaves—" sun- beams " as the natives call them. Gorgeous birds flit from bough to bough. Now and then, you may come upon hundreds of peacocks sitting still in the noon-day heat, each bird upon its favourite perch, a withered bough, its long train of green and gold and purple catching the glimpses of sunlight through the leaves, while thousands of gaudy parroquets scream and flutter, bits of bright green and yellow and scarlet amongst the darker green of the foliage. Whole menageries of monkeys chatter, and swing, and jump in the branches; and there, too, sometimes is to be seen the fitful flight of the most lovely of all birds, the bird of Paradise, with its spray-like plumage silvered in the sunshine, hovering as if it had no feet to touch the earth, or was too beautiful for earth, as the old fables said.

Somewhere from the green depths of the forest—the jungle, as it is called in Anglo-Indian patois—amongst the discordant scream and chatter of birds and monkeys, and the hum of innumerable insects, there comes the sweet merry note of a songbird. It is the pretty little tailor-bird, singing at her work. If you could see her, you would find her deftly stitching together leaves for her nest with a cotton- thread of her own twisting, and singing as she sews. And there, too, is the still stranger weaver-bird, who lights up her nest with fire-flies every night, fastening her live candles with clay to the twigs that make the door-way of her pendent nest, her mate going to sleep by the light of the same fairy tapers, which he has arranged for himself upon each side of his perch.

Almost more beautiful even than the birds and flowers are the butterflies, flying, not in the sunshine, but in the shade of the moist foliage of the jungle. There is one with wings six inches across, as large as many an English bird, which flutters over the acres of delicious blue heliotrope, with upper wings of deep velvet-black, and under wings of sheeny yellow, through which the sunshine passes. Another butterfly has the same black velvet wings, but all dropped with vivid crimson spots; and, more beautiful than all, in the spray of the waterfalls, its gauzy wings kept moist by the water, is the lovely spectre butterfly.

There are no tigers or hyenas in the jungles of Ceylon. At night the air is heavy with the scent of the sweet night-blowing moon-flower, and many another tropical plant which we look at with delight and wonder in our English hot-houses.

And all this world of splendour goes on, ever more beautiful, over hill and plain for hundreds of miles, until, in the interior of the grand island, there are those mountain ranges, whose peaks, like silver in the sun, " Shine down on all the land."

And this is the elephant's home. Here he ranges in great herds through the jungle, the happiest, as he is the wisest and greatest of God's creatures, till tracked out in his forest home, and slaughtered to make sport for Englishmen. Hundreds are made targets for rifle practice, and nothing else, every season; left to be torn by wild beasts, or eaten by vultures, in the depths of the jungle. One English officer alone in a very few years, butchered one thousand four hundred, and was considered, perhaps, the very finest sportsman that ever came out to India. No thought of the utter waste of life, or the pain and useless death of the " game " afoot, ever lowered a keen sportsman's weapon yet. It is " sport;" and there is nothing more to be said. His own intrepidity and skill are all in all; the blood, and pain, and wounds of the killed creature, nothing. Or rather, they help to satisfy that mysterious wild-man instinct, which makes the polished Englishman of to-day as fierce a sportsman as the savage of the bronze and stone periods. Is it true that there are, as some read them, words of prophecy which seem to promise that a time is coming when war between man and beast will be no longer ?1

Thinned as the elephants are by " sport," they are still found ranging in large herds in Ceylon, even near the inhabited parts of the country, although they are chiefly to be found in the interior, and sometimes on very high ground.

At night they wander away upon long excursions, and bathe in the brooks or tanks, which are found far from all modern habitations, far away in the jungle. On coming upon a herd in the day-time, they seem half asleep, "a few browsing listlessly on the trees or plants within reach, others fanning themselves with leafy branches, and a few asleep; whilst the young ones run playfully among the herd, the emblems of innocence, as the older ones are of peacefulness and gravity."

Sir Emerson Tennant, in his charming book upon the "Natural History of Ceylon," says that when the leader of a herd of elephants is wounded, all his " following " do their utmost to protect him from danger; when driven to extremity, they place him in their centre, and crowd in front of him so eagerly that sportsmen have to shoot a number of them to kill him." But when once prisoners, all their loyalty is transferred to their new lords; and no animal devotes himself as an elephant does, to his very utmost, to please his master, even to the most terrible treachery towards his own race. Sir Emerson Tennant tells of a famous decoy elephant, " Seribeddi," who was very clever in beguiling her poor wild friends by her caresses into traps prepared for them ; they would follow her into the corral, or enclosure; and when once she had got them in, she would turn round and begin helping her masters to secure them in the most shameless way. She has been seen, " more than once, when a wild elephant was extending his trunk, and would have intercepted the rope about to be placed on his leg, pushing it aside with her trunk; and sometimes she has pushed her own leg under an elephant's, to hold it up till the noose was round it." She will even kneel upon the wild ones, to prevent their rising, till the ropes are secured. The poor creatures legs are sometimes in wounds for months after they are taken, from the ropes with which they are tied.

The first work an elephant is put to is to tread clay in a brick-field with a tame companion. If he is worked too soon, he will sometimes die of a " broken heart," lying down and dying the very first time he is put in harness. They have been known to do so. Though they make such willing, hard-working servants to man, and may be taken ever so much care of, there is something in slavery which is soon fatal to them. At liberty, they will live a hundred and fifty years, but die almost inevitably within twenty or thirty years after they are taken prisoners. Some, however, have lived in captivity much longer: there was one remarkably fine elephant handed over by the Dutch to the English Government, that was known to have been tamed and at work for more than a century.

Hard work on hot dusty roads must be a cruel life for a poor elephant, after, perhaps, a hundred years of his happy forest freedom.

It seems to be a well-ascertained fact, and it is certainly a most curious one, that wild elephants are never found dead. The natives, in some parts of Ceylon, say that they bury their dead; but there are rumours of a mysterious valley, in the deep jungles eastward of Adam's Peak, reached by a narrow pass with walls of rock on each side, where the elephants go when they feel death approaching. There is said to be a lake in it, by the side of which they lie down to die; but no one alive has seen the place, and no one can find it now. It is not at all impossible that there may be such a place, as some animals are known to have the curious instinct of resorting to some particular spot to die. Darwin says, the llamas have certain circumscribed spots, generally bushy places, and all near water, white with their bones, where they wander to die; and he saw in the Cape de Verde Islands a spot covered with the bones of innumerable goats. It is not impossible that some of the wonderful accumulations of bones in fossil caves may be accounted for by this mysterious instinct, although many of these caverns have been no doubt the lair of wild beasts, and the bones, gnawed and broken as they often are, are evidently the remains of their larders.

When once tamed and taught their work, elephants become so anxious to please their masters that they are very easily managed; and lucky it is, that, his feelings being painfully sensitive, an elephant is very easily made ashamed of himself, for no force could keep him to his work. If he won't do his work properly, he is disgraced by not being allowed to eat his food till his companions have done, or his allowance of sugar-cane (his dessert) is taken away altogether; then he looks so degraded and dejected, that it is impossible not to be sorry for him. A poor old elephant in a menagerie, who was being taught some tricks which he could not manage at all well, was once seen to be practising them by himself in the middle of the night. They always seem to know exactly what they are about when they are at work; when they have balks of timber to pile, they will take them up in their trunks, and fit them into their places as accurately as men could possibly do, walking round their work now and then to see whether it is quite regular, moving any bit of timber, if they think it does not look quite ship-shape. They will raise immense stones, using their tusks as levers, and if those are not powerful enough, will kneel down and push the stones with their heads. An elephant will work by himself, and finish anything he is about, but he won't go on to any other work, unless his keeper is there to tell him, although he may know as well as the man himself what is the next thing to be done; he will stroll away to fan himself with a bough, or throw dust all over his back, to keep the flies off. But if he should be in the very middle of his task, and a bell rings for leaving off, he throws the timber down if he has got it in his trunk, and leaves a stone to its fate, and strikes work at once. No threats or entreaties will make him do any more till the rest time is over.

Sir Emerson Tennant describes a most polite and hard-working elephant, whom he met one evening as he was riding down a forest path in Ceylon. Before he saw anything, he heard a noise like " Umph! umph!" in a very hoarse and dissatisfied grunt. A turn in the narrow ride brought horse and rider face to face with a tame elephant, who was quite alone, and hard at work carrying a heavy beam of timber balanced upon his tusks. The pathway was so narrow that he had to carry the timber with his head all on one side, that the ends might not knock against the trees; and it was so very inconvenient, and such hard work, that it made him make all those exclamations which Sir Emerson Tennant had heard before he saw him. Sir Emerson Tennant pulled up, for the path was too narrow to pass, and his horse was also scary; he says, '" The elephant at once saw the difficulty, and flung down his timber, and voluntarily forced himself back-wards amongst the brushwood, so as to leave a passage, of which he expected us to avail ourselves. The horse hesitated; the elephant observed it, and impatiently thrust himself deeper into the jungle, repeating his grunt of ' Umph.' Still the horse trembled, and again the elephant of his own accord wedged himself further amongst the trees, and manifested some impatience that we did not pass him. At length the horse went by him; and then the elephant stooped and took up his heavy burthen, trimmed and balanced it on his tusks, and went on his way, hoarsely snorting out his discontented ' Umph!"'

I suppose all is not sunshine even in elephantine domestic affairs in those happy forest retreats, for every herd has its outlaws—the poor rogue elephant one hears so much of, whom one cannot help pitying for their solitary wretched lives. They seem to be under some mysterious ban from the rest of their kindred; and with spoiled tempers, turned into unnatural fierceness, manage to make themselves extremely dangerous and disagreeable to the natives. It is the Rogue —the " Hoora Allyas "—who chiefly destroy the crops; and they are always most unsafe to meet in the jungle. They sometimes show a sort of savage eccentricity, which looks very much as if they were elephant lunatics, and had been banished from the tribe for insanity. There must be something the matter, besides the fact of their being crusty old bachelors, which crazes them, for they do the most un-elephant-like deeds in their frenzy fits. One of them was known to have killed and torn limb from limb a young Cingalese woman, and then to have eaten part of the body. A story told in the " Natural History of Ceylon " shows the sort of freakish ferocity which seems to take possession of them. A native told the author that he was travelling with a party of merchants, when they were pursued by a rogue elephant, who killed one of his companions and scattered the rest. Then he came back, and carried the dead coolie on his trunk, with his head dangling down, to where the yokes with the bales of merchandise had been thrown down. Then he put the man on his feet, and put the yoke on his shoulder, steadying both with his trunk and fore-legs. Seeing the man would not stand, he dashed him down and tore him limb from limb. Then he tore open all the bundles of calicos. The same elephant had killed many people previously on that road, and he always tore open their bundles, especially those that contained cocoa-nut oil and ghee, which I suppose be found more to his mind than the calicos.

As outlaws they live and die, their fate being generally, sooner or later, an English bullet, as soon as they come down near the inhabited parts of the island.

A young elephant is the prettiest possible miniature of an old one, except that he has much more hair about him than an old one ever has. They have generally a quantity of shaggy woolly hair about their little bolt heads, which gets scrubbed off by their attendants with pumice-stone and oil, till their skins look like those old-fashioned hair trunks, with the hair worn off.

Kornegalle Jack, the hero of my story, was so called from the place—the interior of Ceylon—where he was captured. The village, which was once a great native capital, lies in the shadow of a wonderful rock, six hundred feet high, in the shape of a couchant elephant, from which it takes its name, " Itetegulla,"— " The Rock of the Tusker. " The jungle comes very close up to it ; and just on the edge of the jungle there lived the young captor, and owner, and tamer, of Kornegalle Jack. There was great fear of malaria upon the lower ground of the village, so the young officer got the Malay soldiers, who are the handiest fellows in the world, to build him a country house on the edge of the forest; and when a country house is built in India, it becomes a " bungalow."

When the bungalow was finished, it turned out that no native would sleep in it at night, from fear of a goblin-haunted Gentoo burying-ground, which was uncomfortably near; so every night the young Englishman was left alone in his empty house, and with no other house within a mile or two, and with the wild-beast-haunted jungle behind him. to do battle with beasts or ghosts, or the more probable peril of native robbers, and with only his dauntless British bravery to guard him. And those Indian bungalows are very different from our barred and bolted houses; the rooms generally all on one floor, the windows opening without glass into verandas, so that it was no impossibility that he should wake up from sleep to see the glare of savage wild-beast eyes upon him, or find himself half strangled by a native assassin.

The morning always found him safe; but still I think it must have been a relief to the extreme solitude of the night when he had caught and tamed his little elephant, who, though no protector, soon became his inseparable and devoted companion. The history of his capture was rather pitiful, for, poor little fellow ! if it had not been for his filial feelings, he would have been a wild elephant to the end of the story. He was a tiny creature, running by the side of his huge mother, when his future master first caught sight of him in the depths of the jungle. He fired, and brought down the old one. As soon as she fell, the little creature showed the most terrible distress, running round, and caressing her dead body with his little trunk, and would not let any one come near her. However, he was caught at last, and a kind of crib or immense cage having been put together for him, a triumphal procession set out through the jungle towards the bungalow, the prisoner being carried, cage and all, upon the shoulders of the natives. When he arrived, the Malay soldiers soon knocked up a kind of stable for him. He was, it was supposed, just six months old, and about as high as an ordinary dinner-table, and the most ferocious little wretch that ever was seen. He would let no one go into his stable, and for two or three days sullenly refused any food. He must have been nearly famished before he gave up the heroic idea of starving to death, and condescended to drink off a bucket of buffalo's milk ; dipping his little trunk into the bucket, he sucked it full of milk, and then spouted it into his mouth, as if he knew all about it, though it must have been his first attempt at such grown-up ways. In a short time, the Baby Elephant had rice-water mixed with his milk to thicken it ; the next step was being promoted to boiled rice, and then he began to get young tender grass and plantains. His master allowed no one but himself to feed him for the first few weeks, and he became very gentle with him, long before he would allow any one else to come near. If people tried to come into his stable, he would rush at them, beat them with his little trunk, and try to knock them over.

He was a close prisoner for a long time; but as soon as he got a little quieter, he used to be picketed by the hind legs in the compound, the enclosure round the bungalow. At the end of two months, being thoroughly tamed and domesticated, he was allowed to ramble about the house and grounds as he pleased; but his favourite place was by his master's side, whether he was in the house or out of it. He followed him like the most faithful dog for long distances, even on horse-back, and was furious if he found he had been left behind. Of course, this devotion of his was rather troublesome sometimes, especially on one memorable occasion, when he shocked his master, and scandalized the congregation, and disconcerted the clergyman, by coming to church. He bad broken out of the compound, where he was supposed to have been left quite safe, found out which way to follow by some mysterious instinct, and then demurely walked up the aisle, and stood by his beloved master's side. He would have stood there quietly through the longest sermon, but of course it would not do, so Mr. — had to get up and walk home with him.

When his master was at home in the heat of the day, Jack generally stood by him, fanning him; his fan was a chowry, a soft tassel-like brush used by the natives to whisk away flies, or else a green branch, with which he would brush the flies away from his master and himself.

Elephants, whether wild or tame, always seem the most fidgety animals, every one having some peculiar movement, either swinging their legs or rolling their heads, which they begin the moment they have nothing else to do. Little Jack's form of fidgets was rolling his head from side to side, and flapping his great ears, as he stood, the picture of goodness and gravity, for hours by his master, turning himself most usefully into a punkah.

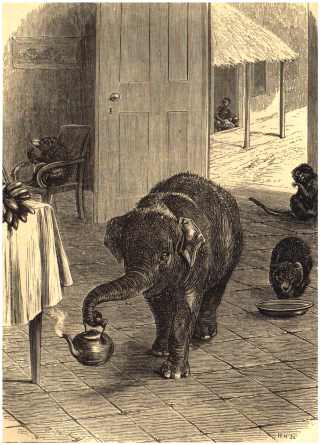

The earliest dawn of day always found Jack wide awake; and the first thing he did was to go and awake his master. All the rooms opening on to the verandah, he had only to walk up to the open windows, and give his little trumpet-call ; and if that would not do, he walked in and repeated it by the bed-side; and if that would not do, he awoke him effectually by putting the end of his little trunk very gently on his forehead. There was no use pretending to be asleep after that; and after being sure that his master really meant to get up, the elephant went to see about breakfast. The cook house—Anglice, the kitchen—is always a separate building in India ; and it was Jack's first morning duty to go there and fetch the kettle.

As soon as he saw his master was ready for breakfast, he went to the black cook, who gave him the kettle with a cloth wrapped round the handle. He carried it into the house, and put it carefully down on a mat by his master's side; and when the tea was made he picked it up and took it back again. He did this quite safely for a long time; but one day, either from not balancing the kettle properly, or some other mishap, he poured some of the boiling water on his feet. He screamed, and made the most terrible hullabaloo, dashed down the kettle, and rushed into the house to his master for help. After that, though little Jack was too good to refuse to do his morning duty, he evidently thought it a very dangerous bit of work; and he used to walk very slowly, with his trunk stretched quite straight in the most ridiculous way, and the kettle dangling at the end of it, carrying it as clear of his toes as he possibly could. A portrait of Jack in this predicament is still extant. He stood by the table all breakfast-time, eating his own breakfast, a bunch of delicious fresh plantains always waiting for him on the table, and at which he twinkled his eyes approvingly, but never touched till the kettle business was finished. Breakfast over, he sallied out to visit the hospital with his master, who was the military surgeon at Kornegalle. He was always warmly welcomed by the sick soldiers, who used to be very much amused at him as he walked every day gravely up to their bedsides, standing with an anxious and inquisitive look by his master, as he examined and prescribed for his patients. What his interest in it all could be, it is impossible to imagine; but there was something in the ceremonies of feeling pulses, and looking at tongues, which Jack was never tired of observing; and he always watched to see how the men took their medicine. Perhaps he found the wry faces rather amusing. Little he thought it might be his own fate some day; for elephant " Vets " have a way of giving their patients the very nastiest doses, which they will swallow in a way that would be an example in the best-regulated nursery.

Jack had the air of a grave and anxious medical student, as he walked the wards with his master, looking as if he tried to learn and remember what he saw; and he showed one day that he really had thought about it. One of the native orderlies had developed a peculiar talent for giving pills, in a short, sharp, and decisive way, that sounds the very perfection of military discipline and smartness. He gave the word of command that mouths were to be open, and then dropped the pills down their throats. The patients, generally Malay soldiers, were very successful in taking their pills, and not getting choked, as Englishmen would infallibly have been; but one day, a poor fellow was choked, and coughing violently, the pill fell at the elephant's feet, who at once picked it up, and held it daintily in the finger-like end of his trunk. It struck his master, who saw what he bad done, that he would give the pill quite as well as the orderly, whom he had so often watched; so the patient's mouth was ordered to be very wide open, and touching his trunk, his master said, " Give it him. Jack, give it him !" The elephant instantly put the end of his trunk to the man's mouth, and giving a whiff, effectually blew the pill down the soldier's throat.

When hospital duty was over, he sometimes accompanied his master to make some morning calls in the Cantonment. He would stand where he had been left in the verandah, immoveable as a sentry on duty, until he thought that all reasonable time for a call was over. Then he gave a sharp, impatient trumpet, as much as to say, " What in the world is keeping you so long ?" And if that would not bring out his. friend, he would sometimes glide noiselessly into the house, and startle every one by repeating his queer little trumpet-call at the very drawing-room door.

Jack was a never-ending source of amusement to the little native boys, who generally kept him in good-humour by bringing him presents of plantains, sweetmeats, and those famous rice-cakes, the chuppaties, which were sent, like the lighted brand, through all India, as a symbol for rebellion upon the rising which became the fearful mutiny. Jack was always much pleased and flattered by these attentions of his playfellows; but the more mischievous ones sometimes tormented him dreadfully, and made him very angry; and on one occasion a horrid boy pricked him very badly in the trunk with a long sharp thorn. This was too much for Master Jack, who promptly resented the insult. The boy had got off as quickly as he could, and away dashed Jack after him, making a charge right through the fence of the compound. It would be difficult to say which was greater, the terror of the boy or the rage of the elephant. The boy ran for his life, screaming and shouting with fright. Jack galloping after him at the top of his speed, trumpeting with fury. The boy got first to the bazaar, as the native villages are called, and plunged into one of the first houses for refuge. But Jack bided his time, although his enemy had escaped him that day.

Two months afterwards, his master was riding through the bazaar, and Jack trotting along by the side of his horse as usual, when he suddenly dashed forward at a native boy who was quietly walking on in front; and before the boy could tell what had happened, he was tumbled head over heels, and would have been trampled and injured by the elephant, if he had not been very promptly rescued. Jack's time had come; for the boy, when picked up, proved to be his enemy, who had thoroughly deserved his fright, which I dare say it made the elephant happier to have given him, for they have a long memory for insults, and revenge them years afterwards, if they have a chance.

But Jack had other tormentors; there were two little pet bears of his master's, which were for a long time the plague of his life. These little hairy monsters would persist in alternately biting and scratching his soft legs, and then finish the performance by trying to climb up his tail. Jack thought it a great nuisance for a long time, but eventually he became very good friends with them, and all three would play together in the most amusing way. But worse even than bears or boys, the very crowning misery of his life in those early days, was a tame monkey, a beautiful little creature of the Entelles tribe, who was another pet of his master's, and who was determined to make Jack a riding elephant for himself, and after many a hard fight at last got his own way. The monkey must have watched the Mahouts, the elephant-drivers, sitting upon the shoulders of their animals, or almost upon their necks, as they seem to do, and thought it would be very enjoyable ; but the difficulty was to make Jack enter into the joke, and to carry his Mahout quietly. The first thing to be done was to get a mount; so when Jack would be gently dozing or fanning himself under a tree, the monkey would steal unobserved behind him, climb the tree very quietly, and drop suddenly from one of the branches on to his back. This at first used to terrify the elephant, and he would rush across the compound, trumpeting furiously. Then came the tug of war, the elephant making the most violent efforts in his rage and alarm to get rid of his rider, lashing his trunk round to unseat him by a blow, which the monkey had to avoid by throwing himself into all sorts of absurd attitudes. It was the most masterly bit of horsemanship; for besides all the efforts which a restive horse makes to unseat his rider, there was the additional difficulty of the elephant's trunk, which had to be avoided at all risks. Many a ride the monkey had in this desperate fashion; and at last he broke his charger in by sheer pluck and perseverance, and after a time the elephant would allow him to mount whenever he liked, and would take him for a ride round the compound, the monkey sitting on his neck like his Mahout, flapping away the flies from his friend's head with a green branch.

The most curious result of Jack's education was his taking, with all the delight of a dog, to field-sports. A dog and his master share the same keen hunting instinct, for (although hardly perhaps a polite way of putting it) they are both carnivora; but an herbivorous elephant taking to " sport " is a most grotesque anomaly. It may have been only his intense delight in his master's exploits; hut certainly Jack came latterly to think that there was no pleasure in life like a day's shooting, and he allowed himself to be trained into the most accomplished retriever.

When he had once got his head full of these sporting expeditions. Jack used to be found at the very first dawn of day standing by his master's bedside, impatiently trying to awake him with a touch on his forehead of his soft little trunk; and when he saw him dressed, his shot-belt and powder-flask slung on, and his gun in his hand, all ready to sally out with him into the jungle, his delight knew no bounds.

Forty years have gone by since then, but still the memory of those morning rambles remains as vivid as ever to one of the happy ramblers. Poor Jack's enjoyment of sublunary things, and so, I fear, of anything at all, is long since over; but he enjoyed that glimpse of Eden in his own elephantine way as long as it lasted, and, we can but hope, had no forebodings beforehand, or many regrets after all was past and over.

The beauty of a tropical dawn in a forest scene in Ceylon might well be a picture of that primeval earth-splendour, which we call Paradise. As the stars pale one by one in the clear sky (a bluer, higher heaven than we ever see), the morning flushes over all the east with a sudden glory. " Heaven and earth are full of the majesty of Thy Glory;" no other words so fit the hour and scene; all is so pure, so beautiful, so fresh from God Himself. Then the great golden sun shines up on the horizon, or over the violet mountain ranges, throwing along the park-like glades of the jungle long level shadows of banyan-trees, palms, and a hundred other strange, beautiful, often gigantic trees. Leaves and flowers glitter with dew-drops trembling and flashing back prismatic colours in the level sunbeams. Nothing can be more delicious, after perhaps a sultry night, than the fresh sweetness of that morning air, perfumed with the scent of lemon-grass and innumerable flowers, while the crowing of the jungle-cock, the cooing of doves, and flutter and chatter of screaming parroquets, and all the other gorgeous-coloured but unmusical tropic birds, tells of the awakening of the joyous forest life to its very depths.

By the tanks, those wonderful works of a gone-by civilization, wherever they are found in the depths of the jungle, the fresh footprints of elephants, deer, and wild beasts may often be traced in the mud of the banks; and when the sun first touches the water, long lines of scarlet and white flamingoes are seen wading on their stilt-like legs in the shallow water, on which the lovely rose-lotus is floating, and whole fleets of white and sky-blue water-lilies, while the banks are fringed with graceful reeds, and the still more graceful bamboo, waving in the light morning breeze.

The jungle came almost up to the back of the bungalow, so the young officer and his pet soon found themselves, on their morning excursions, far enough away from all sound or sight of human life, in the depths of that lovely forest scene. They paced on side by side, till they came within sight, often at a great distance, of their game. Jack would mark down a peacock or a jungle-fowl a long way off, and instantly turn himself into a stalking-horse for his master, on the shortest possible notice. After marking down the bird with his quick eye, he would begin to stalk it in the most scientific way. Jack's acting was so inimitable that he always on these occasions seemed to be walking anywhere but towards his game, as he went along in a sideway kind of fashion, with his head innocently turned the other way, but always getting nearer and nearer. The part he was acting, his role, was that of a poor little elephant taking a solitary walk in the jungle, nothing at all for a peacock or jungle-fowl to be frightened at, while all the while the little wretch was concealing his master, creeping along with his deadly gun on the other side of him, ready to fire the moment he had got within range. Peeping from time to time over his back, Jack had a sign from his master to stop when the game was within shot; and then, though eager with excitement, like the consummate actor he was. Jack went on with his clever by-play, looking about in the most unconcerned way, or flirting with a tussock of grass, while his master steadied his gun upon his back. Then came the sharp report, and away he went, wild with delight, crashing in his rolling canter through shrubs and long grass to pick up the bird, which he would bring back carefully in his trunk.

Sometimes, when Jack was away looking for a wounded bird, his master would climb a tree to hide from him. When he came back, and could not find him, he would rush frantically about, searching everywhere for him, stopping every now and then to listen, and trumpeting furiously, in loud strong notes that echoed far and near. He never, however, went to any great distance, and always returned to the spot where he had left his master; and when at last he saw him, his delight knew no bounds; he would run round and round him, wag and swing his little tail in a ridiculous manner, flap his great ears, and twine his trunk caressingly about him.

We are so used to the affection of our pet animals, that little we think of the strangeness of the love they give us; and yet, if we thought of it, nothing can be more wonderful than for a creature to give up its strongest instincts, its natural love of its kind even, as a tamed animal will often do, for the love of its master—its return, the half-pitiful kindness it gets, by fits and starts only, from its captor and tamer. " Ah me! what faithfulness God hath put into the heart of His creatures!"

It was on one of those mornings in the jungle that Jack had his chance of freedom, of perhaps a hundred years or more of life and liberty, had he known it, instead of thirty uncomfortable years of captivity. But the spell of that strange new affection was too strong, and he rejected his one chance of turning into a wild elephant again, and ended his days after all in a menagerie.

It was one morning, when Jack was pacing along by the side of his master, when they suddenly encountered a troop of about thirty wild elephants, passing across a piece of open ground about two hundred yards in front. The troop halted, but did not show any disposition to charge. There were several young ones amongst them, and two about Jack's age came playfully towards him, while he went to meet them, the remainder of the herd quietly looking on. Jack's master was dreadfully afraid that he was negotiating for a retreat with his tribe: he had nearly given up all hopes of his ever coming back, when suddenly the parley seemed over, the little coterie parting; the wild young ones went back to the herd, and Jack came back to his master, looking lovingly up in his face, as much as to say, " Did you really think I was going to desert you ?"

Poor little fellow! well would it have been for him if he had gone away, once for all, and been lost in the depths of his grand forest home, where he would never have been heard of more; his happy days were to be soon over, and, like the history of most pet creatures, his subsequent fate was something of a tragedy. Eighteen months after Jack's capture, the young officer had to prepare for his return to England. He gave his poor little pet to Lady B., the wife of the. Governor of Ceylon, and if all tales are true, there were some tears shed at parting with his little friend; and as elephants share with us that most human expression of grief, if poor little Jack had known what that last good-bye meant, he would probably have cried too. Tears will sometimes drop freely from a poor wild elephant's eyes, in the distress and grief of the first days of his captivity.

No chronicler tells the tale of the next eight years of Jack's life. He was a large elephant when he came to England, a present from Lady B. to the Zoological Gardens in the Regent's Park. Here he found himself shut up for life in a sort of barred loose box, a wild beast at last, after all his loving companionship with his master, standing to be stared at, for weeks and months and years, in the most hopeless, aimless monotony.

He became a great favourite with the visitors, for whose amusement he had to go through a series of tricks. He was most gentle and docile, and he had a keeper to whom he became much attached. Poor creature, he was observed to be always trying to find something to do, to relieve the monotony of his imprisonment; and as, according to Dr. Watts, somebody always does find mischief for idle people to do, poor Jack, in his supreme idleness, hit upon a grand bit of mischief, which lasted him his life-time. This was pulling his stable to pieces. His ceiling was of perfectly smooth planks, fitting closely together, and apparently quite impervious to any tool of his; but having once struck Jack that it would be amusing to pull it down, he set to work upon the most scientific principles. The ceiling was very low, so he first punched a hole into the boards with his tusks, and then inserting the finger-like end of his trunk into the holes, he could pull the boards away. He seems to have been always trying some amateur carpentering upon his dull stupid prison walls; and as an Irishman would say, "Small blame to him, poor fellow!"

His daily rations at this time sound something portentous. His bill of fare, besides all the cakes which he gathered as backsheesh from the visitors (no small item on some of the popular days), was a truss and a half of hay, forty-two pounds of Swedish turnips, a mash consisting of three pounds of boiled rice, a bushel of chaff, and half a bushel of bran, ten pounds of sea-biscuit; and even this was not quite enough, for Jack generally finished every night by eating up his bed.

Jack understood natural history rather better than the Fellows of the Zoological Society, for one of their decrees was that he was to be treated like the lions and tigers, who fast on Sundays, for the convenience of their own constitutions, as well as their keepers' Sunday's rest; but they certainly did not seem to have consulted sufficiently the exigencies of an herbivorous creature, to whom the alternate gorging and starving of the camivora was simply an impracticability. Poor Jack was starving when they stopped his Sunday food, and he made them at last aware of their stupidity by the most judicious measures of agitation. For two or three successive Sunday nights the noise he made all night in his stable prevented the keepers getting any sleep. Finding that this hint was not taken, he went a little further next time, and so bestirred himself, that, like other agitators who have known exactly how far to go, he carried his point; for he made an attack upon his door with such good-will and effect that they were obliged to get up in the middle of the night to feed him. After that demonstration of physical force Jack always got his meals in regular order every Sunday. He grew to be one of the largest Asiatic elephants ever seen in England. He stood almost as high as an ordinary room, nine feet six to the shoulder. The only recreation he could ever get was a slow saunter now and then along the gravelled paths of the Gardens, and this cramped, unnatural life at last began to make him very ill. A most miserably painful disease, white-swelling, appeared on his knees. Standing as he did, day and night, for weeks and months together, with all his enormous weight pressing upon the diseased knee-joints, his sufferings must have been piteous. He got so bad at last, that he never lay down.2 He stood for two whole years without once being able to lie down, trying to rest himself at times, as well as he could, by putting his trunk across the front bar of his cage, and so taking the weight in some measure off his legs. His sufferings affected his whole nervous system, and he became very irritable. His favourite keeper, too, had been changed, and this annoyed him very much, for it is always a matter of the greatest difficulty to induce an elephant to take to a new man. None of the keepers at last durst go near him; the only way they could ever clean out his box was by placing his food in the back partition, when he would open the door, go in, and carefully shut it behind him, almost as if he felt the sight of the men would bring on his fits of ferocity, and he shut the door to prevent seeing them. This he did every day, until he knew his front room was ready for him, and then he went back. At last, he was so agonized with pain, and made so fierce by it, that it was thought best to put him out of his misery.

Once only did Jack and his beloved master see each other again. Eight years had gone by, and Mr. — had heard nothing of his favourite from the time he had left him behind in Ceylon, when one day, something about a large elephant he was looking at in the Zoological Gardens reminded him of his little Jack: he went up to him and was warned by the keepers not to go too near; but he spoke to him, and the elephant looked observant; it was not, however, till he called him by his Cingalese name, that Jack knew who was there. The name, unheard for eight years, struck upon some chord of memory, for he instantly showed that he remembered it, and knew who was speaking, though he had been such a little fellow when he had seen his master last. He showed much pleasure at seeing his beloved master, who had been to him his fate, for if it had not been for. that day's shooting in the jungle, Jack would have probably had a hundred years of life and liberty in his glorious summer land, still before him. Many will think complacently that the rifle-shot which changed all that, and contributed unwittingly an elephant to a menagerie, contributed much to the amusement of hundreds of people, and something to their information; and we ought, of course, to feel—if we had properly-constituted minds—that the cause of science justifies anything, from spitting butterflies on corking-pins to shutting up elephants to die by slow tortures in menageries. Having died a martyr in the cause of " useful information," the bones of poor Jack still contribute to the same laudable purpose. They stand, a gaunt, grim framework of leg-bones, ribs, and ponderous skull, a practical lesson to the visitors of the British Museum, in osteology; also, if they thought of it, of mortality—for the creature shared with us the twin mysteries of life and death. Well might Arnold say, so overwhelming was the mystery of the animal creation, that he did not dare to think of it. Suffering, we hope, in the providence of God, is to us discipline; but what is it to them ? And of all the wrongs that are done under the sun, the cruellest, because the most undeserved, fall to the share of the innocent dumb creatures: for our touch is pain, ending in disease, disaster, and death. Whether we mean it or not, the inevitable law is too strong for us, the ghastly fact remains, and meets us everywhere, that man's dominion over the brute creation is a kingdom of suffering. What it means we cannot tell, there is a jar somewhere; " the whole creation groaneth and travaileth in pain together until now," but He who has created, has seen and pitied, and it will not always be so; for evermore, as one thinks of it, like a note of harmony in the sharp discord, comes the fulness and tenderness of the thought so beautifully expressed by Edward Irving, " Ah me! what faithfulness hath God put into the heart of His creatures; what pure love must be in His own!"

1 Immediately after the prophecy of peace, when "the lion shall lie down with the lamb," come the words, " They shall not hurt nor destroy in all my holy mountain : for the earth shall be full of the knowledge of the Lord, as the waters cover the sea."—Isaiah.ii. 9.

2 Elephants will frequently stand for months after they are first taken; when they lie down, they are beginning to get tame.

| Cwestiynau? Sylwadau? Beth ydych chi'n meddwl am y tudalen hwn a gweddill y wefan? Dywedwch yn y llyfr ymwelwyr. Questions? Comments? What do you think about this page and the rest of the site? Tell us in the guest book. |