| | Hafan Home | | | | Chwilio Search | | | | Hanes a dogfennau History & records |

|

EVERYBODY has heard of Bob, the fireman's dog, who joined the brigade of his own accord, who barked before the engines to clear the way, who had a nose for a fire like another dog for a rabbit, and who, amongst other exploits, on one occasion, showed his full comprehension of his duties as a fireman, by dashing into a burning house, and, at the risk of his own life, saving that of a cat. Bob emerged from all that smoke and fire behind him, singed and blackened, but carrying in his mouth his rescued cat. He also saved the life of a child, by his persistency in scratching and whining at the door of a room in a burning house, which was supposed to be empty; but Bob knew better, and never gave up till he got the door opened, and the child, who was found lying insensible on the floor, was carried away to safety. Bob wore to the day of his death a broad brass collar with an inscription in his own honour. He appeared on the platform at one or two public meetings of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, and when his time came, and that fatal engine crushed him to death, he died mourned by the men of his own corps, as a dear old friend and true hero.

The hero of my story bore the same illustrious name, and, alas! had the same disastrous fate. He, too, like most great geniuses, dogs or men, chose his profession with a strong intuitive instinct; and, apparently, without any particular reason. Who can tell why one great man takes to painting, another to making poetry, and another to making, spinning-jennies ? Or why an inland boy, who never heard the dash of a wave on the shore, or heard a sea-bird's scream, or saw anything more like a ship than a coal-barge on a canal, yet becomes so haunted by the sea, that he invariably ends by running away, and gets himself afloat and into all the delights of a tarry jacket as soon as may be ? It must be the. same with dogs, or why did Bob, the fire-dog, take to fires, or my hero, Bob, the soldier, to soldiering ? Bob enlisted as seriously and really as any recruit who takes the shilling, pins ends of ribbons in his cap, and calls himself there and then a warrior. Bob rose from the ranks. He was a butcher's dog, and so, though no doubt he had plenty to do, he had plenty to eat, and is sure to have had rather a prosperous life of it. He drove cattle and sheep, but he ate them too, and the cow-heels that he had bitten at in the way of discipline, he probably got, finally, as his own perquisite; unless, indeed, his master was that very Windsor butcher who, tradition says, was " tripe and cow-heel purveyor to her Majesty." Then, I suppose, the cow-heels went to Court. But whether he got them or not, scraps and tit-bits of the poor beasts he helped to drive came in his way as well as his master's; and you know how fat those dreadful " blue butchers " always do look! It was certainly not for want of a dinner, like so many other poor recruits, that Bob took the shilling. He joined at Windsor. At that time (the spring of 1853), the first battalion of that splendid regiment, the Scots Fusilier Guards, were quartered in the Castle.

How Bob found them out at first, I don't know; perhaps he went to the barracks with beef. But when once he had seen the red-coats and heard the music, it was all over with Bob: he never condescended to bite at cow-heels again. His head was as completely turned as any young belle's in a garrison town. Bob now saw what he was meant for; he was a dog who had found his future. He took every opportunity of returning to the barrack-yard to see more of military life; and he was constantly being fetched home from the barracks by the butcher. I don't know how long this sort of thing went on; but the end of it was, that Bob tired out the butcher. He got tired of fetching his henchman home, and Bob never went home again. From that time his career became a military one, and the history of his life is that of his regiment.

His new comrades adopted him at once; and in about a month afterwards, when, upon a sunny June day, the whole battalion marched to Chobham Camp, Bob had the proud satisfaction of marching out at their head, as the dog of the regiment. It certainly was a rise in life for an ambitious dog like Bob; promotion enough to turn any dog's head. He who only a month before had to get an honest living by biting at the heels of unruly cows, or worrying at the throats of misguided but ill-foreboding pigs, who would not, like the ducks in the ballad, " come and be killed,"—he, that very Bob, marched now to the roll of the drum and the sound of military music with all the grand scarlet coats and bear-skinned caps behind him, as he stepped on with the band, the dog of that very crack regiment, her Majesty's Royal Scots Fusilier Guards!

Can you not fancy how Bob's always rather retroussé nose curled higher ?—how his rather stumpy tail stuck out on end, as he passed by those cur acquaintance, who would have been out with all the rest of the world, in Windsor streets, to see the show that day ? Bob could not and would not then have spoken to the best friend of them all. For one thing, he would have felt it a breach of duty to leave the ranks, in line of march; but more than that, he must have felt at that moment that he was leaving his old butchering ways and doings far behind him. And yet, though he might be a little proud, Bob deserved his destiny, for he had known his own mind, and stuck to it like a fine dog as he was; and more than half the battle is to know what you want to do, and can do, and then do it with all your might.

Bob stuck to his duty like a man. He fell in with the strict regulations of the service at once, and was famous for his soldier-like punctuality. The chronicle of his life (probably drawn up by one of his officers) tells how " he was always first on parade;" and then goes on to say, " that when the duties of the day were over, no old soldier could be more expert at foraging." What that means exactly, I cannot say. It seems very much as if Bob had had to get his rations how he could; as " foraging " always gives one the idea of hungry soldiers in an enemy's country, rushing into houses and coming out with stolen loaves of bread and sides of bacon. It cannot surely mean that Bob carried out his military furore in raids of this sort; perhaps it only means that he had to make out a living by looking up contributions in the soldiers' and officers' huts and tents—perhaps he even showed his black nose at mess. His foraging is sure to have been easy work, for soldiers as well as sailors are very kind to anything they make a pet of; and I dare say Bob might have had fifty dinners a day, if he could have eaten them.

He was a great favourite from the time he joined, but he showed no partiality to any one in particular; he would not go out of barracks with a single individual except on duty.

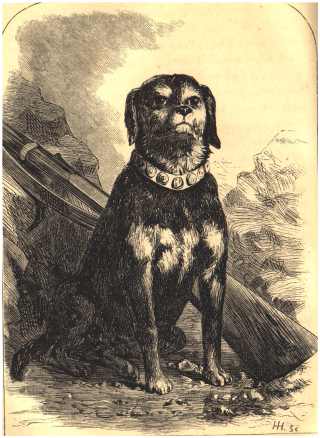

Our readers will like to know what our hero was like, as at present they only know him by a turned-up nose and stumpy tail, and they were only his weakest points. He was a black dog, with tan points, and a dash of white on the chest. Why a dog who has any tan about him invariably has two spots of it over his eyes, remains, as the author of " Our Dogs " truly says, "amongst the deepest mysteries of tan." They give a wonderful amount of expression to the eyes beneath them, and Bob had them very conspicuously. He had a handsome head, and he was a strong, powerful dog, smooth skinned, with a coat like black satin. Such breadth of chest and strength of limb are seldom seen. He was rather a middle-sized dog as to size, and as to breed, what his friends called him I cannot imagine. He was bigger than any terrier, though he may have had terrier ancestors on one side; but there was probably a bull-dog mésalliance on the other. There must evidently have been a flaw somewhere in the pedigree, but still, every one would have said he was a handsome dog; and looks it still, though only a stuffed dog now, and all hay inside. But this is sadly forestalling his history.

It was the year after Bob joined that the Crimean war broke out, and his regiment was under orders for the East. The last day of England came, and the gallant officers and men of the Scots Fusiliers marched out of camp, with their band playing the old home airs. But most of them never came home again !—in two short years, or less than that, more than half of those grand-looking men were in their graves, the Crimean grass and wild flowers above them. But none thought of that then, as they marched out with sound of drums, and all the clang and clash of military music, and who but Bob himself at their head! They were to embark in her Majesty's ship Simoom, and whether Bob was forgotten or not in the confusion, I don't know, he seems to have had to shift for himself; but he got himself on board somehow. And here, as his chronicler says, his career was very nearly put an end to. " What dog is that ?" said the first lieutenant; and no one in particular claiming him, the word was passed, " throw him overboard," and the sailors would have had him over the side in no time, if some of the soldiers had not heard the order, and come to the rescue. Then it was explained that, though Bob belonged to nobody, he belonged to everybody; and so he was allowed his passage to the Crimea with the rest of the troops.

How he bore his voyage, this, his history, does not tell. I have no doubt he had mal-de-mer, and wished he was a butcher's dog again, if his esprit-de-corps would have allowed him. His memorialist goes on to say, that he served at Malta, Scutari, and Varna, and in Bulgaria. From the last place, the regiment re-embarked for the Crimea. Whenever they were going to sea, Bob's comrades seem to have been particularly careless, to say the least of it, about him, for here we find him in difficulties again. He had to look after his own embarkation, apparently, and get himself on board how he could; and the result was what might have been expected: as he could not hail the right transport, he got on board the wrong one. But now it was shown to all the world what a person of consideration Bob had become in his regiment, for, after he had been reported missing, and it was discovered where he was, an escort of officers went off in a boat to fetch him back!

By this time he had evidently become indispensable. Gallantly wagged that somewhat stumpy tail, no doubt, as Bob, looking over the bulwarks of the " wrong ship," saw the blonde moustachios of the right men, his own beloved officers, who were waiting for him to come over the side to row him to his "Own" again.

Then came the landing on that fatal Crimean shore. Bob was the first to land. Soon. all England rang with the news of the battle of the Alma, and English hearts beat high with hope and fear at the sight of those grim lists of dead and wounded which filled the morning papers. At the Alma, the Scots Fusilier Guards were in the thick of the mêlée; they were for hours forcing their way up a steep hill, driving the Russians back before them, and in the very teeth of a tremendous battery.

Down they went by hundreds, and the Welsh Fusiliers by their sides fought as gallantly, and got mowed down as fearfully. Together, they drove the Russians from their guns, and then the great battle of the Alma soon became a victory. The French had been winning their way up that deadly hill also, and the Russian army was thoroughly beaten. But that fatal hill behind them was strewed with dead and dying. An officer of the Scots Fusiliers was cut down, fearfully wounded, when some Russian Lancers coming up, struck their lances through him, and another Russian thrust his sharp bayonet through, as he thought, the officer's head ; but he had not made allowance for the tall bear-skin, so the bayonet only pinned it to the ground, and that wound, which must have been fatal, the officer escaped, and he survived all the rest, and came back once more to England.

This was Bob's first battle. I wonder what he thought of it—whether he did not think it worse butchery than what he had been accustomed to at Windsor. The descriptions of that Alma battle-field, after the day was over, exceed in horror all that was ever told, of those grim and ghastly scenes.

Poor Bob, I suppose, got lost in the battle ; he lost sight of the colours, somehow ; it is not possible that he ran away —one must not believe it. But at all events, when the day was over, he did not answer to the roll-call, and he was reported in the list of missing. Many a Guardsman, looking amongst the heaps of dead for his comrades, I dare say looked too for the shining black coat of the dog of the regiment, thinking his friend might have been knocked over in the melee. But Bob was not there; for, after making a flank march through an enemy's country on his own account, he rejoined the battalion at Balaclava. How he found his way across miles and miles of an entirely unknown country is wonderful. Then, at all events, his soldier-like foraging must have come useful. He was at the battle of Balaclava, and looked on, I suppose, at the charge of "the gallant six hundred," when the " cannon to right of them, cannon to left of them, vollied and thundered;" and the troopers rode back a few handfuls of men. " Some one had blundered!" The soldier-dog appears again at the famous battle of Inkermann, when, in the dawn of the lowering November morning, the grey Russians crept up under cover of the grey fog, and, on their hands and knees amongst the bushes, had got by hundreds close up to the sleeping soldiers, until a trumpet sounded the alarm, and the men sprang to their feet to find themselves in a fight for life and death. The day came, the fog cleared off, and hours went by, and they were fighting still, mowing the Russians down before them, as fresh grey battalions still swarmed up the hills to fight and die. At last that day, too, was won. I have heard that when those poor Russian soldiers were searched before they were buried, besides the invariable little picture of their patron saint, which every man wore round his neck, it was quite a common thing to find a kitten buttoned up in his coat. Poor fellows! those fair-haired Russians, though they fight so obstinately, are strangely gentle at heart; and I fancy the kittens, to them, were like a bit of home in the midst of war. Still, there is something mysterious about it. What became of the kittens who grew up, as they could not have gone into battle with old cats in their coats ? It would have been against " regulations," and there would have been no hiding the cats though they hid the kittens. It was not exactly kind to the kittens, either, to take them into battle, but they could not help it, unless they left them to die. I have heard of several, of these " warrior kittens " who were taken from the bodies of their poor dead matters, and were brought to England by English officers. It seems to have been after that fiercest of the fights, the battle of Inkermann, that Bob got his medal. He was in the battle, and tried to serve his country by chasing spent cannon-balls and shell. Well for Bob it was that he did not catch them—a shell, at all events, or his career of glory would have ended in his being blown to " smithereens " for his country.

It was for so distinguishing himself, and for his general good conduct, that "Bob was awarded a medal," which, I suppose, as he had not got a buttonhole to hang it from, he must have hung round his neck like a lady's locket. Through the days and nights of that dreadful time which followed, when his gallant friends who had looked so magnificent in old days in England had got from bad to worse, until they were as shabby as tramps, poor fellows, to look at—and were, I am afraid, nearly as hungry too, because again "some one had blundered "—Bob served with them in the trenches. In adversity of any kind, an old friend is the best company; and I dare say to many a poor fellow through those dark nights in the wet, cold trenches, it seemed cheery and home-like to have Bob's head to pat now and then, as he paced up and down on his dreary beat, with every chance of being knocked over at each turn by a shell or cannon-ball. But at last the horrible war was over, Sebastopol had fallen, and every one was coming home, except those who would never come home again. I wonder if Bob missed kind hands which had patted and fed him, or whether he had so many to do those little attentions for him that he had no time to love or regret any one excessively; but I think he must have had many misgivings over those who came back no more.

Bob himself came back to England, after all his battles, a veteran, without a scratch about him, and his good-conduct medal as a trophy. He ought to have had his clasps for Varna, Scutari, and all the rest of the famous places, but it does not appear that he got them. Then came the proudest day of his life, as well as of hundreds of others. Two years before, the Guards had marched out of London to that dreadful war, and now, thinned by bad food, and cold, and disease, and wounds, those who were left of them were coming back once more. In the bright sunshine of the summer day the gallant regiments marched through the crowds of their countrymen who had come out to meet them. Their Queen was there to see them too, as they passed before her palace windows; and all, from her Majesty to the poorest creature in the crowd, with all their hearts, welcomed home the gallant Guardsmen. I wonder if her Majesty the Queen, or the crowd, observed our hero—the head and front of that triumphal entry—for there he was. Bob was marching at the head of his regiment into London, after sharing the fortunes of his corps through such eventful times, with his good- service medal round his neck. Like the last days of most famous soldiers, Bob's subsequent career is no way remarkable. He appears to have done duty in London and at Portsmouth, and once more to have gone back to Windsor, where, if he was at all like other old warriors, he no doubt fought his battles over again, and if so, he may have left traditions amongst his old compatriots, the Windsor curs, of his Crimean campaigns. When quartered in the Tower of London, which is close to the river, he used to go backwards and forwards to the " West end " by the steamboats, and, as he was well known to the boat proprietors, no objection was made. What Bob wanted in the West end I don't know, unless he went to call upon his officers occasionally. He would have been heartily welcome, I am sure, though he would have looked but a bluff old soldier in a West-end drawing-room, and would certainly have turned up his nose at the Skyes he met there. He had a large circle of acquaintances and admirers. At guard mounting at St. James's, or at the reviews and field-days in Hyde Park, his portly form and decorated breast attracted considerable attention. Poor Bob's eventful life was nearly over. How often one hears of a sailor who has been knocking about all his life at sea, getting drowned at last in some muddy little river at home, or an old soldier who has been pounded at by cannon-balls in a score of battles, who shoots himself with his own gun out ferreting at last, or a fox-hunter who breaks his neck in a morning's ride, after years of cross-country work! Poor Bob's fate was very similar.

After " eating glory," as a Frenchman would say, after playing with spent balls on a furious battle-field, and all his perils by land and sea, Bob was killed like any cur by being run over in the streets. The regiment was in London; it was one morning early in February, 1860, when he was marching out at its head as usual, that it happened, and " poor Bob," as his historian says, " was killed, to the great regret of the whole regiment."

" Many were the expressions of regret as the poor dog was conveyed past the battalion by a drummer, who carried him to the Buckingham Palace guard-room."

The Fusiliers showed their love for their friend by putting him amongst the trophies in the United Service Museum, at Whitehall. He sits in a glass case, wearing a collar of white leather round his throat, such as soldiers' belts are made of, studded with the buttons of his regiment; a gift, most likely, of some of the men to their favourite. His history is written on a board below him.

He looks wonderfully life-like. He who has immortalized him (stuffed him, I suppose one ought to say, only it sounds unpleasant in a hero's history) has caught admirably, and given the look which one almost thinks Bob must have caught from his soldier friends. As he sits there, with his strong fore-legs planted firmly down each side that broad chest, and looks out straight before him, he has the most intrepid, soldier-like bearing possible, and looks as if he was doing outpost duty for all England. And, as if he had not had enough of battles in his life-time, he has always to sit looking out over the field of Waterloo, the model of which, like a great map, is just before him. On one side is the skeleton of Napoleon's horse, Marengo, and a polished hoof of his conqueror's horse, Copenhagen; and many another relic of battle-fields are all around him.

Down below, in the lower rooms, are models of all the ghastly contrivances for killing everybody the world ever saw, from the tomahawk to the latest sixty-pounder Armstrong. Old soldiers are patrolling as attendants. So Bob has war everywhere about him still; and though he has not found a soldier's grave, he has perhaps done as well, enshrined, as he is, by the loving regret of his soldier-friends, amongst such warlike associations, and amongst, too, the sad and touching relics of the battle-fields of their country. So we thought as we read his history, took a hasty sketch of him, and then " left him alone in his glory." I conclude my biography of Bob with the following lines, which are reprinted by the kind permission of their accomplished author, the present Professor of Poetry in the University of Oxford.:—

Go, lift him gently from the wheels,

And soothe his dying pain,

For

love and care e'en yet he feels,

Though love and care are vain;

‘Tis sad

that, after all these years,

Our comrade and our friend,

The brave dog

of the Fusiliers,

Should meet with such an end.

Up Alma's hill, among the vines,

We laughed to see him trot,

Then

frisk along the silent lines,

To chase the rolling shot.

And when the

work waxed hard by day,

And hard and cold by night,

When that November

morning lay

Upon us like a blight,—

And eyes were strained, and ears were bent

Against the muttering north,

Till the grey mist took shape and sent

Grey scores of Russians forth.

Beneath that slaughter wild and grim,

Nor man nor dog would run ;

He

stood by us, and we by him,

Till the great fight was done.

And right throughout the snow and frost

He faced both shot and shell;

Though unrelieved, he kept his post,

And did his duty well.

By death

on death the time was stained,

By want, disease, despair;

Like autumn

leaves our army waned,

But still the dog was there.

He cheered us through the hours of gloom,

We fed him in our dearth;

Through him the trenches' living tomb

Rang loud with reckless mirth.

And thus when peace, returned once more,

After the city's fall,

That

veteran home in pride we bore,

And loved him one and all.

With ranks refilled, our hearts were sick,

And to old memories clung;

The grim ravines we left glared thick

With death-stones of the young.

Hands which had patted him lay chill,

Voices which called were dumb,

And footsteps that he watched for still

Never again would come.

Never again: this world of woe

Still hurries on so fast;

They come

not back, 'tis we must go

To join them in the past.

There with brave

hearts and deeds entwined,

That may not be forgot,

Young Fusiliers

unborn shall find

The legend of our pet.

And when some grey-haired soldier tells

How, through that night of fear,

The city tolled its sudden bells,

Warning that death was near.

How

with the fog, that shrouded foe,

Boiled round us, nigh, and nigher,

Like

smouldering smoke, which gathers low,

To burst in floods of fire.

Thence wandering through the past at will,

Before our children's eyes,

To frame each living picture still,

Just as he sees it rise.

How,

bearing doom to many a soul,

After a long delay,

The great siege of

Sebastopol,

Began at break of day.

How, with full knowledge of the fate

That dogged their desperate track,

The Balaclava horsemen straight

Rode into Hell and back.

How o'er

the bleak hill's blood-stained crest,

As boys at foot-ball run,

The

Guards and Highlanders abreast

Raced for the Alma gun.

How sudden on each fevered bed

Delight, like summer broke,

When soft

hands propped the dying head,

And tender voices spoke.

How then,

awakening from despair,

At length the soldier knew,

That to her children

suffering there

The mother's heart beat true.

Marked by the medal his of right,

And by his kind, keen face,

Amid

these histories, grave and bright,

Poor Bob shall keep his place.

And

never may our honoured Queen,

For love and service pay

Less brave, less

patient, or more mean

Than his we mourn to-day.

Sir Francis Doyle.

| Cwestiynau? Sylwadau? Beth ydych chi'n meddwl am y tudalen hwn a gweddill y wefan? Dywedwch yn y llyfr ymwelwyr. Questions? Comments? What do you think about this page and the rest of the site? Tell us in the guest book. |