| | Hafan Home | | | | Chwilio Search | | | | Hanes a dogfennau History & records |

|

THERE is a mystery in the whole atmosphere of the breakfast table this morning. The Squire, his sons, and nephews all wear the same pleasant look of elation. Something has happened; but whatever it is, it is not to be spoken. The happiness is evidently of that deep, concentrated nature that needs no words, a thing to be felt, not talked of. And they evidently do feel it as they eat their breakfast almost in silence. But what does it all mean, when, after a long interval of happy thought, the Squire says, à propos of nothing, " Strong little beggars; better luck with this lot, I hope. Knock over a few rooks for them after breakfast, Charlie."

A nod from Charlie, but nothing to explain the matter. Not till the after-breakfast dispersion do I, the uninitiated, venture to ask the least sporting member of the household what sort of " little beggars " made everybody so happy this morning.

" Oh! foxes in the old earth in the Beech Wood; an old Mrs. Fox been disturbed somewhere, and migrated to us, babies and all. But don't say a word about it. I ought not to tell; nobody talks about that sort of thing, you know."

So as the mystery of mysteries they remained, for it evidently was défendu to ask anything more about them; but it was very pleasant, though puzzling, to see what happiness they gave. All day long, and for many a day after, the influence of those foxes was felt over the whole house. A calm, too serene to be ruffled, by the death of lambs, by the laming of horses, even by an epidemic among the young pheasants, had settled over the Squire. He walked and rode his rounds through field, and farm, and stable, with a look that told of a " happy dream he did not care to speak." The Squire was beyond the reach of lesser griefs while those foxes were safe in his own Beech Wood. For him the world of his fellow Christians was divided into those who loved foxes, and those who loved them not; those who would give them all, and those who, like the unreasonable old women in the village, grudged them all things, even their own pet hens. Darkly and gloomily brooded the Squire over the perils with which the plots of those bereaved women might surround that earth in the wood. He believed the villagers capable of anything—traps, poison, even of turning down a mangy fox into his covers, that all the rest of the foxes might catch it.

" We never deeply love that for which

We do not also greatly fear."

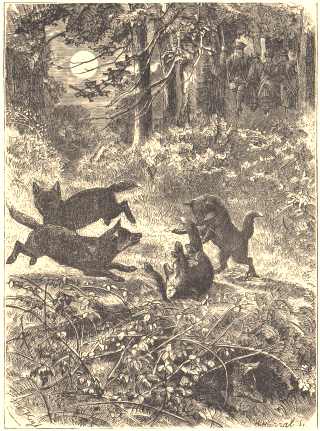

It was so with the Squire during those happy, anxious weeks. There came a day when it came to be hinted rather than said, that those foxes might be seen. It was evidently thought almost too good news to be true, and more than ever was it a thing not lightly to be spoken of. We knew that night after night the Squire and. his sons, sometimes one, sometimes all three, disappeared for two or three hours periodically at dusk; and we guessed where they had been, but never asked. The look of happiness they brought back with them could be from nothing else but the sight of the foxes. Imagine the thrill of astonished delight when, at dinner (of course after the servants had left), the Squire said, " Put on your waterproofs and come along with me to-night." Should we too see the foxes! it meant that or nothing. With an utter absence of decorum, a sad want of tact, some one had almost said " To see the fox . . . . ?" but was stopped by a nod from the Squire. " Ay, ay, you'll see the prettiest little beggars you ever saw in your life." Ten minutes afterwards, and. we were on our way to the Earth, on the war trail, walking in Indian file, led by the Big Chief himself. Through the lawn, where the dew lay heavy on the grass, and the house looked strangely mysterious and still in the light of the " gloaming " as we looked back upon it; over the brook, sleepily gliding past the water-weeds, and under the arch of the little bridge, where the poplars stood like warders stiff and tall, into the deep shade of the Beech Wood at last. The ground cushioned with reddened leaves, and. patches of velvet-green moss, soft and silent under our feet, only the wood pigeons now and then "whished" away from a tree as we passed under it; and far away, from the opposite wood came still the pleasant jangle of the rookery. The rooks are all saying good-night, and ten thousand good-nights make a good deal of croaking music. Are we ghosts or Indians? stalking grim and grey in the shadow of the darkened wood—Indians, I think; and the Big Chief dangles a mass of tumbled-up-together poor young rooks in his left hand, which will do very well in this light for his last bunch of scalps on the war path. But we shall never do for squaws. Our cloaks, our grey masquerade all put on for those wretched foxes, will catch in the brambles, and when the sticks crackle under our feet, in a way they should certainly never do under Indians', the Squire hears and turns and with a perfectly imploring gesture, enforces silence. More sticks and a perfect labyrinth of brambles, over which tall legs stride, but through which we scratch, and at last, at last, a little open glade round which we skirt in the shadow of the trees, and reach a great clump of thick beech. Here one of the grey-cloaked ones is suddenly and deftly picked up by the tall Squire, and placed like a young bird on a branch. No, upon looking closer, it is not a branch, but a sort of swing, a big stick swung by a cord amongst the branches, evidently a luxurious contrivance of the Squire's for watching the " Earth " in peace. Some people might think perching upon poles, like apes amongst the branches, not so pleasant, and it certainly is not in the long run, but here, so perched up aloft, the Squire kept those mysterious vigils. Here then we were to watch in the silence as he had watched every night for a fortnight, and would every night for the next six weeks, our eyes fixed upon the brambles, till we should see—what we shall see. We had been apes and baboons for an hour ; an Indian Fakeer in the first six months of his sixty years' penance, could not have been more uncomfortable—nothing but the Squire's stern grey-blue eyes kept us from dropping off our perches—when the brambles moved, and something moves across the shadow, and coming right for us, into the open space, where it is much lighter, we see a fine old vixen fox. The Squire's grey eyes are a sight to see ; every stern line has softened down, till his whole face is a smile over that fondly-loved old fox, who creeps on stealthily, and not at her ease, as if she rather thought the Squire was there, and ungratefully wished him anywhere! She stops and looks suspicious, but sees us not, and steals on in her stealthy walk, and disappears under some fern. But who comes here ? Four of the merriest little madcaps that ever tumbled head over heels and raced after each other's brushes. Here are the cubs; here are the unutterably-beloved " little beggars " themselves. They come racing into the arena, as if they were going to show off for our especial amusement. Beautiful, graceful little creatures, fuller of fun and tricks than the tricksiest of kittens, their coats are just getting a reddish tint, and they have pretty white tips to their brushes. Common words though are not for them. Foxes have neither feet nor tails, nor tips to their tails; for them all these appendages are pads and tags and brushes. Only we may, it seems, call their heads, heads. Little reck those poor little Fetishes who wear those sacred brushes—which cause more hard riding than many a well-fought battle—of all the adoration which is beaming down upon them from the beech trees. Half an hour by the clock, and three by our discomfort, we have watched them at their gambols, when. from under the fern, where she disappeared, steals the old vixen hack to the bairns, with a soft grey bunny as the children call it, with a white ring round its neck, hanging across her murderous jaws. This sobered the cubs, or at least put a stop to their play, and turned them into the savage little carnivori that Nature made them. Tearing and tugging at the. rabbit, they all disappeared together under the brambles, and swiftly and silently we got down from our trees, and resumed our war-path through the now darkened wood.

The house might have fallen in upon the Squire, and he would not have cared about it that night. For another month, at least, the foxes diffused the same air of general happiness through the household. To save that beloved vixen trouble, rooks and rabbits died by dozens. The Squire and his sons did it all, taking the affairs of that precious nursery into their own hands. The keepers were not allowed to interfere, a dark cloud of suspicion hanging over that department just at that time, in consequence partly of their mothers all owning hens in the village, and also of their own incredible but suspected partiality for pheasants versus foxes.

But sunshine does not last for ever, and ours came to an end at last. It was

a bright morning in June, the Squire strode into the hall, with his gun in his

hand, looking as if he had seen a ghost. He laid down the gun upon a table,

looking utterly wretched, but also angry. There was hardly an attempt at " talk

" that morning; it was felt to be too indecorous while that look fixed

itself on the master's brow. It was Jupiter Tonans in glower and gloom. But,

good gracious, what was it, what could make the Squire, what could make

any man, look like that ? When at last I make my next neighbour understand that

it really is too alarming to sit still, and not know what is the matter, this is

what is revealed in a scared whisper:—

" Cubs; it's the cubs."

" Are the

cubs dead ?"

" No—mange; they have got the mange."

And, alas! how the gloom deepened to dark on the Squire's brow, as he caught the tragic word which told his trouble. He remained long deeply unhappy; but I think they (the cubs) survived it—at least I know some of them did—and I suppose after all there were plenty more cubs in the world, for the Squire was to be seen five days a fortnight a very few months afterwards, in his oldest pink coat with the claret-coloured tails, with all his gallant pack, and the whole hunt behind him, brushing through the gossamer, cub hunting. The Squire was trying, with all his skill and cunning, with the aid of sixteen couple of savage hounds, to kill his pet cubs. He would have hanged a man as high as Haman if he had caught him trying to do the same thing in another way; but now his musical hallo comes through the wood, as he gallops down the ride under the beech-trees, and hounds on all those murderous savages, without a single misgiving, upon his last pet cub. The poor little cub scurries about in a helpless sort of way, through and through the wood, scared back by outsiders, placed for the purpose, whenever it attempts to get away, till at last one hears it is " chopped," which, perhaps, means made mincemeat of, for that is exactly what has happened—or will happen very soon. The cub was run into close to the Earth, and his playroom—the grassy little glade near the beech trees—made a pretty theatre for the last scene of his poor little life. The Squire, dismounted, holds him up at arms' length above his head, a limp and bloody mass of reddish fur, the hounds all yelling and tearing at him as, with a screech like a demoniac, he pitches the cub into the middle of the pack, who quarrel, and fight, and yell, and tear worse than ever, and then it is all over. He has killed his cub, and had him eaten; and the Squire looks as pleased as the day when, on that very spot, under the beech trees, he first watched that poor "little beggar" at play. It was all as it should be. Had not that fox died as a fox should die ?

One wonders what a fox must have had to get over before he joined a pack of hounds himself; but one actually hunted regularly with harriers for three years in Northumberland, and another lately, in Cardiganshire, constantly went out shooting. Charlie, the Welsh sporting fox, was a most beautiful fellow, and unusually tame. He arrived as a tiny cub, with close grey fur—and very little of it—and a rat-like tail (in that embryo state it was certainly not a brush), and about as big as a good-sized kitten. He lived either in his master's pocket, or in a little kennel in the flower garden, where he ran in and out of the doors and windows of the house at his own pleasure. Tea with cream and sugar was his breakfast, and a boiled rabbit his dinner. A whistle at the windows brought him scudding along the garden, with his brush level behind him, till he came with a scamper into the room. Then he would swing his brush, like a dog wagging his tail, and whine and whimper with pleasure, with the prettiest, most winning look in his eyes, as he came to be petted and played with. The words, " Sugar, Charlie!" always arrested him, and he would stop and trot to the sideboard, and look up and wait for the bits of sugar which generally awaited him there, and then begin again a series of gambols round and round the room, over the chairs, and under the tables, till he usually ended by jumping into his master's arms, and being carried away in triumph into the garden. Then he got wilder than ever, racing from one end of the walks to the other, or, with his brush in his mouth, rolling over and over down the steep grassy slope; he would repeat this feat as long as he had anybody to watch and applaud him, until some other fancy struck him. He would snatch handkerchiefs, or gloves, or hats, and carry them off in triumph over the garden; but shoes and boots, for which he hunted pertinaciously in bedrooms and dressing-rooms, went off sometimes as pairs, sometimes as odd ones in Charlie's mouth to his favourite lair in the shrubberies; and he ate more leather in this way, and especially indiarubber, in the shape of goloshes, than could possibly have been good for him. His frolics were not always even as innocent as this. A stately flock of Shanghai hens lived near, and promenaded all day close to that very shrubbery where Charlie chose to live. The hens were old and fat, and walked with that matronly and deliberate air Shanghai hens always do. So of course one by one they vanished, and no questions were asked; Charlie was welcome to anything, except perhaps the grand old Shanghai cock, and he was more than a match for him; he could not walk any faster than his old hens, but he fairly cowed the fox by his huge size and loud voice. Charlie used to lie watching him by the hour, lying flat with his head between his feet, and the old bird standing on guard, not daring to move, and croaking his expostulations with his enemy, who, however, never dared a dash at the owner of those grand double spurs. One day Charlie was met by his master trotting along with a little bunch of brown feathers in his mouth, which proved to be a pet bantam hen. This was rather too much, so he had to give it up; and just as his master stooped to take it out of his mouth, he rushed round and picked his pocket, scampering away with the handkerchief. The hen was put down, and Charlie chased and captured, and the handkerchief rescued; but away he went back, and caught up the hen, scampering off with her, and disappearing in the depths of a shrubbery where no one could follow, and of course not a feather was ever seen more.

He had plenty of his own kith and kin to play with. Many a frolic was watched, when his friends the wild cubs came down from the hill for a game of play with him in the twilight. There were a lot of cubs that year about, and one day Charlie's master had a strange encounter with an old paternal fox, who was kindly catering for his family in a novel way. He met him face to face on a narrow path, leading a turkey hen by her long throat—the old hen trotting along by the side of the fox as if she had quite agreed to the arrangement, and was going to save him the trouble of carrying her, by walking with him all the way to his cubs in the cover, which was their destination. Of course her fortunate meeting with her master " changed all that." A whistle near the laurels—Charlie's favourite spot for sleeping—always brought him creeping out in a few moments, gaping and looking very pretty and very sleepy, as if he had just awoke, and then he would wake quite up, and curl himself round his master's feet, whining with delight as he caressed him, and often licking his fingers like a little dog. He would follow for any distance, when he was taken out for a walk, but not at all like a dog. He always, on a road, seemed to prefer running along the hedge bank, for the sake of the field-mice, which he pounced on one after another in the most extraordinary way—catching, and killing, and eating five or six in the course of a very short evening walk. His greatest delight was being taken out with a gun. Even if he had not been called, he sometimes made his way to the sound of his master's gun, and he never seemed scared at the report as he trotted by his side, and picked up the rabbits like a little retriever.

He was just grown up—grown out of his cub days, and tamer than ever, and petted by everybody—when one day he was missed. It was October, and the fox-hounds would be meeting soon in the neighbourhood, and if Charlie was wandering he would certainly get into trouble. So there was great despair when day after day he never came back to whistle or call, his rabbit untouched, and his tea untasted, showing he had never been home. Nothing was ever heard of him more. No one had even the consolation of knowing that he had died as a fox should die. If he had given a good run—if he had scurried for twenty miles over hill and bog, till his pretty red-brown coat was draggled with sweat and mud, and his heart was almost burst—it would have been dying as a fox should die. He should have been killed "in the open," run into by the hounds, and there died a rapid, bloody, glorious death, amongst thirty-two pair of savage jaws, and have been carried home, honourably, in fragments; his brush in a lady's hat, his head in Brusher's or Bobadil's jaws, and his pads in everybody's pockets.

But not for poor Charlie was the glory of having fulfilled the destiny of a fox.

His brush was never hung in hall or bower; his memory, and the runs he

gave, never toasted by the men who loved him as only fox-hunters can love

a fox, and who would have killed him exultingly and cheerily, as only

fox-hunters ought to kill him. Ehue! -

" Save me from my friends."

Did Charlie think so ? He never came home again!

THE END

| Cwestiynau? Sylwadau? Beth ydych chi'n meddwl am y tudalen hwn a gweddill y wefan? Dywedwch yn y llyfr ymwelwyr. Questions? Comments? What do you think about this page and the rest of the site? Tell us in the guest book. |